Summary

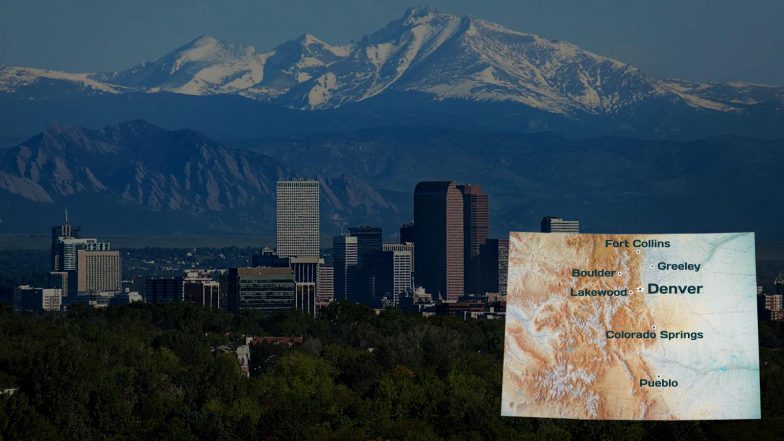

Colorado is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the Great Plains. Colorado is the eighth most extensive and 21st most populous U.S. state. The 2020 United States Census enumerated the population of Colorado at 5,773,714, an increase of 14.80% since the 2010 United States Census.

Colorado is bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas to the east, Oklahoma to the southeast, New Mexico to the south, Utah to the west, and touches Arizona to the southwest at the Four Corners. Colorado is noted for its vivid landscape of mountains, forests, high plains, mesas, canyons, plateaus, rivers, and desert lands. Colorado is one of the Mountain States and is a part of the western and southwestern United States.

Denver is the capital and most populous city in Colorado. Residents of the state are known as Coloradans, although the antiquated “Coloradoan” is occasionally used. Colorado is a comparatively wealthy state, ranking eighth in household income in 2016, and 11th in per capita income in 2010. Major parts of the economy include government and defense, mining, agriculture, tourism, and increasingly other kinds of manufacturing. With increasing temperatures and decreasing water availability, Colorado’s agriculture, forestry and tourism economies are expected to be heavily affected by climate change.

OnAir Post: About Colorado

About

Source: Wikipedia page

Colorado[b] is a landlocked state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, and part of the Southwestern United States, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas to the east, and Oklahoma to the southeast. Colorado is noted for its landscape of mountains, forests, high plains, mesas, canyons, plateaus, rivers, and desert lands. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the Great Plains. Colorado is the eighth-largest U.S. state by area and the 20th by population. The United States Census Bureau estimated the population of Colorado to be 5,957,493 as of July 1, 2024, a 3.2% increase from the 2020 United States census.[12]

The region has been inhabited by Native Americans and their Paleo-Indian ancestors for at least 13,500 years and possibly much longer. The eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains was a major migration route for early peoples who spread throughout the Americas. In 1848, much of the Nuevo México region was annexed to the United States with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The Pike’s Peak Gold Rush of 1858–1862 created an influx of settlers. On February 28, 1861, U.S. president James Buchanan signed an act creating the Territory of Colorado,[1] and on August 1, 1876, president Ulysses S. Grant signed Proclamation 230, admitting Colorado to the Union as the 38th state.[2]

Denver is the capital, the most populous city, and the center of the Front Range Urban Corridor. Colorado Springs is the second-most populous city of the state. Residents of the state are known as Coloradans, although the antiquated “Coloradoan” is occasionally used.[13][14] Colorado generally ranks as one of the top U.S. states for education attainment, employment, and healthcare quality.[15][16][17] Major parts of its economy include government and defense, mining, agriculture, tourism, and manufacturing. With increasing temperatures and decreasing water availability, Colorado’s agriculture, forestry, and tourism economies are expected to be heavily affected by climate change.[18]

History

The region that is today the State of Colorado has been inhabited by Native Americans and their Paleo-Indian ancestors for at least 13,500 years and possibly more than 37,000 years.[19][20] The eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains was a major migration route that was important to the spread of early peoples throughout the Americas. The Lindenmeier site in Larimer County contains artifacts dating from approximately 8720 BCE. The Ancient Pueblo peoples lived in the valleys and mesas of the Colorado Plateau in far southwestern Colorado.[21] The Ute Nation inhabited the mountain valleys of the Southern Rocky Mountains and the Western Rocky Mountains, even as far east as the Front Range of the present day. The Apache and the Comanche also inhabited the Eastern and Southeastern parts of the state. In the 17th century, the Arapaho and Cheyenne moved west from the Great Lakes region to hunt across the High Plains of Colorado and Wyoming.[citation needed]

The Spanish Empire claimed Colorado as part of Nuevo México. The U.S. acquired the territorial claim to the eastern Rocky Mountains with the Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803. This U.S. claim conflicted with the Spanish claim to the upper Arkansas River Basin. In 1806, Zebulon Pike led a U.S. Army reconnaissance expedition into the disputed region. Colonel Pike and his troops were arrested by Spanish cavalrymen in the San Luis Valley the following February, taken to Chihuahua, and expelled from Mexico the following July.[citation needed]

The U.S. relinquished its claim to all land south and west of the Arkansas River and south of 42nd parallel north and west of the 100th meridian west as part of its purchase of Florida from Spain with the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819. The treaty took effect on February 22, 1821. Having settled its border with Spain, the U.S. admitted the southeastern portion of the Territory of Missouri to the Union as the state of Missouri on August 10, 1821. The remainder of Missouri Territory, including what would become northeastern Colorado, became an unorganized territory and remained so for 33 years over the question of slavery. After 11 years of war, Spain finally recognized the independence of Mexico with the Treaty of Córdoba signed on August 24, 1821. Mexico eventually ratified the Adams–Onís Treaty in 1831. The Texian Revolt of 1835–36 fomented a dispute between the U.S. and Mexico which eventually erupted into the Mexican–American War in 1846. Mexico surrendered its northern territory to the U.S. with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo after the war in 1848; this included much of the western and southern areas of Colorado.[citation needed]

Most American settlers first traveled to Colorado through the Santa Fe Trail, which connected the U.S. to Santa Fe and the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro southward. Others traveling overland west to the Oregon Country, the new goldfields of California, or the new Mormon settlements of the State of Deseret in the Salt Lake Valley, avoided the rugged Southern Rocky Mountains, and instead followed the North Platte River and Sweetwater River to South Pass (Wyoming), the lowest crossing of the Continental Divide between the Southern Rocky Mountains and the Central Rocky Mountains. In 1849, the Mormons of the Salt Lake Valley organized the extralegal State of Deseret, claiming the entire Great Basin and all lands drained by the rivers Green, Grand, and Colorado. The federal government of the U.S. flatly refused to recognize the new Mormon government because it was theocratic and sanctioned plural marriage. Instead, the Compromise of 1850 divided the Mexican Cession and the northwestern claims of Texas into a new state and two new territories, the state of California, the Territory of New Mexico, and the Territory of Utah. On April 9, 1851, Hispano settlers from the area of Taos settled the village of San Luis, then in the New Mexico Territory, as Colorado’s first permanent Euro-American settlement, further cementing the traditions of New Mexican cuisine and New Mexico music in the developing Southern Rocky Mountain Front.[22][23]

In 1854, Senator Stephen A. Douglas persuaded the U.S. Congress to divide the unorganized territory east of the Continental Divide into two new organized territories, the Territory of Kansas and the Territory of Nebraska, and an unorganized southern region known as the Indian Territory. Each new territory was to decide the fate of slavery within its boundaries, but this compromise merely served to fuel animosity between free soil and pro-slavery factions.[citation needed]

The gold seekers organized the Provisional Government of the Territory of Jefferson on August 24, 1859, but this new territory failed to secure approval from the Congress of the United States embroiled in the debate over slavery. The election of Abraham Lincoln for the President of the United States on November 6, 1860, led to the secession of nine southern slave states and the threat of civil war among the states. Seeking to augment the political power of the Union states, the Republican Party-dominated Congress quickly admitted the eastern portion of the Territory of Kansas into the Union as the free State of Kansas on January 29, 1861, leaving the western portion of the Kansas Territory, and its gold-mining areas, as unorganized territory.[citation needed]

Territory act

Thirty days later on February 28, 1861, outgoing U.S. President James Buchanan signed an Act of Congress organizing the free Territory of Colorado.[1] The original boundaries of Colorado remain unchanged except for government survey amendments. In 1776, Spanish priest Silvestre Vélez de Escalante recorded that Native Americans in the area knew the river as el Rio Colorado for the red-brown silt that the river carried from the mountains.[24][failed verification] In 1859, a U.S. Army topographic expedition led by Captain John Macomb located the confluence of the Green River with the Grand River in what is now Canyonlands National Park in Utah.[25] The Macomb party designated the confluence as the source of the Colorado River.[citation needed]

On April 12, 1861, South Carolina artillery opened fire on Fort Sumter to start the American Civil War. While many gold seekers held sympathies for the Confederacy, the vast majority remained fiercely loyal to the Union cause.[citation needed]

In 1862, a force of Texas cavalry invaded the Territory of New Mexico and captured Santa Fe on March 10. The object of this Western Campaign was to seize or disrupt Colorado and California’s gold fields and seize Pacific Ocean ports for the Confederacy. A hastily organized force of Colorado volunteers force-marched from Denver City, Colorado Territory, to Glorieta Pass, New Mexico Territory, in an attempt to block the Texans. On March 28, the Coloradans and local New Mexico volunteers stopped the Texans at the Battle of Glorieta Pass, destroyed their cannon and supply wagons, and dispersed 500 of their horses and mules.[26] The Texans were forced to retreat to Santa Fe. Having lost the supplies for their campaign and finding little support in New Mexico, the Texans abandoned Santa Fe and returned to San Antonio in defeat. The Confederacy made no further attempts to seize the Southwestern United States.[citation needed]

In 1864, Territorial Governor John Evans appointed the Reverend John Chivington as Colonel of the Colorado Volunteers with orders to protect white settlers from Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors who were accused of stealing cattle. Colonel Chivington ordered his troops to attack a band of Cheyenne and Arapaho encamped along Sand Creek. Chivington reported that his troops killed more than 500 warriors. The militia returned to Denver City in triumph, but several officers reported that the so-called battle was a blatant massacre of Indians at peace, that most of the dead were women and children, and that the bodies of the dead had been hideously mutilated and desecrated. Three U.S. Army inquiries condemned the action, and incoming President Andrew Johnson asked Governor Evans for his resignation, but none of the perpetrators was ever punished. This event is now known as the Sand Creek massacre.[citation needed]

In the midst and aftermath of the Civil War, many discouraged prospectors returned to their homes, but a few stayed and developed mines, mills, farms, ranches, roads, and towns in Colorado Territory. On September 14, 1864, James Huff discovered silver near Argentine Pass, the first of many silver strikes. In 1867, the Union Pacific Railroad laid its tracks west to Weir, now Julesburg, in the northeast corner of the Territory. The Union Pacific linked up with the Central Pacific Railroad at Promontory Summit, Utah, on May 10, 1869, to form the First transcontinental railroad. The Denver Pacific Railway reached Denver in June of the following year, and the Kansas Pacific arrived two months later to forge the second line across the continent. In 1872, rich veins of silver were discovered in the San Juan Mountains on the Ute Indian reservation in southwestern Colorado. The Ute people were removed from the San Juan Mountains the following year.[citation needed]

Statehood

The United States Congress passed an enabling act on March 3, 1875, specifying the requirements for the Territory of Colorado to become a state.[27] On August 1, 1876 (four weeks after the Centennial of the United States), U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant signed a proclamation admitting Colorado to the Union as the 38th state and earning it the moniker “Centennial State”.[2]

The discovery of a major silver lode near Leadville in 1878 triggered the Colorado Silver Boom. The Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 invigorated silver mining, and Colorado’s last, but greatest, gold strike at Cripple Creek a few months later lured a new generation of gold seekers. Colorado women were granted the right to vote on November 7, 1893, making Colorado the second state to grant universal suffrage and the first one by a popular vote (of Colorado men). The repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act in 1893 led to a staggering collapse of the mining and agricultural economy of Colorado, but the state slowly and steadily recovered. Between the 1880s and 1930s, Denver’s floriculture industry developed into a major industry in Colorado.[28][29] This period became known locally as the Carnation Gold Rush.[30]

Twentieth and twenty-first centuries

Poor labor conditions and discontent among miners resulted in several major clashes between strikers and the Colorado National Guard, including the 1903–1904 Western Federation of Miners Strike and Colorado Coalfield War, the latter of which included the Ludlow massacre that killed a dozen women and children.[31][32] Both the 1913–1914 Coalfield War and the Denver streetcar strike of 1920 resulted in federal troops intervening to end the violence.[33] In 1927, the 1927-28 Colorado coal strike occurred and was ultimately successful in winning a dollar a day increase in wages.[34][35] During it however the Columbine Mine massacre resulted in six dead strikers following a confrontation with Colorado Rangers.[36][37] In a separate incident in Trinidad the mayor was accused of deputizing members of the KKK against the striking workers.[38] More than 5,000 Colorado miners—many immigrants—are estimated to have died in accidents since records were first formally collected following an 1884 accident in Crested Butte that killed 59.[39]

In 1924, the Ku Klux Klan Colorado Realm achieved dominance in Colorado politics. With peak membership levels, the Second Klan levied significant control over both the local and state Democrat and Republican parties, particularly in the governor’s office and city governments of Denver, Cañon City, and Durango. A particularly strong element of the Klan controlled the Denver Police.[40] Cross burnings became semi-regular occurrences in cities such as Florence and Pueblo. The Klan targeted African-Americans, Catholics, Eastern European immigrants, and other non-White Protestant groups.[41] Efforts by non-Klan lawmen and lawyers including Philip Van Cise led to a rapid decline in the organization’s power, with membership waning significantly by the end of the 1920s.[40]

Colorado became the first western state to host a major political convention when the Democratic Party met in Denver in 1908. By the U.S. census in 1930, the population of Colorado first exceeded one million residents. Colorado suffered greatly through the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, but a major wave of immigration following World War II boosted Colorado’s fortune. Tourism became a mainstay of the state economy, and high technology became an important economic engine. The United States Census Bureau estimated that the population of Colorado exceeded five million in 2009.[citation needed]

On September 11, 1957, a plutonium fire occurred at the Rocky Flats Plant, which resulted in the significant plutonium contamination of surrounding populated areas.[42]

From the 1940s and 1970s, many protest movements gained momentum in Colorado, predominantly in Denver. This included the Chicano Movement, a civil rights, and social movement of Mexican Americans emphasizing a Chicano identity that is widely considered to have begun in Denver.[43] The National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference was held in Colorado in March 1969.[44]

In 1967, Colorado was the first state to loosen restrictions on abortion when governor John Love signed a law allowing abortions in cases of rape, incest, or threats to the woman’s mental or physical health. Many states followed Colorado’s lead in loosening abortion laws in the 1960s and 1970s.[45]

Since the late 1990s, Colorado has been the site of multiple major mass shootings, including the infamous Columbine High School massacre in 1999 which made international news, where two gunmen killed 12 students and one teacher, before committing suicide. The incident has spawned many copycat incidents.[46] On July 20, 2012, a gunman killed 12 people in a movie theater in Aurora. The state responded with tighter restrictions on firearms, including introducing a limit on magazine capacity.[47] On March 22, 2021, a gunman killed 10 people, including a police officer, in a King Soopers supermarket in Boulder.[48] In an instance of anti-LGBT violence, a gunman killed 5 people at a nightclub in Colorado Springs during the night of November 19–20, 2022.[49]

Four warships of the U.S. Navy have been named the USS Colorado. The first USS Colorado was named for the Colorado River and served in the Civil War and later the Asiatic Squadron, where it was attacked during the 1871 Korean Expedition. The later three ships were named in honor of the state, including an armored cruiser and the battleship USS Colorado, the latter of which was the lead ship of her class and served in World War II in the Pacific beginning in 1941. At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the battleship USS Colorado was located at the naval base in San Diego, California, and thus went unscathed. The most recent vessel to bear the name USS Colorado is Virginia-class submarine USS Colorado (SSN-788), which was commissioned in 2018.[50]

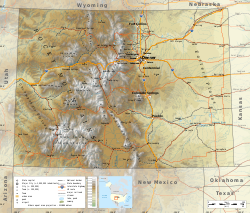

Geography

Colorado is notable for its diverse geography, which includes alpine mountains, high plains, deserts with huge sand dunes, and deep canyons. In 1861, the United States Congress defined the boundaries of the new Territory of Colorado exclusively by lines of latitude and longitude, stretching from 37°N to 41°N latitude, and from 102°02′48″W to 109°02′48″W longitude (25°W to 32°W from the Washington Meridian).[1] After 165 years of government surveys, the borders of Colorado were officially defined by 697 boundary markers and 697 straight boundary lines.[51] Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah are the only states that have their borders defined solely by straight boundary lines with no natural features.[52] The southwest corner of Colorado is the Four Corners Monument at 36°59′56″N, 109°2′43″W.[53][c] The Four Corners Monument, located at the place where Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah meet, is the only place in the United States where four states meet.[52]

Plains

Approximately half of Colorado is flat and rolling land. East of the Rocky Mountains is the Colorado Eastern Plains of the High Plains, the section of the Great Plains within Colorado at elevations ranging from roughly 3,350 to 7,500 feet (1,020 to 2,290 m).[54] The Colorado plains are mostly prairies but also include deciduous forests, buttes, and canyons. Precipitation averages 15 to 25 inches (380 to 640 mm) annually.[55]

Eastern Colorado is presently mainly farmland and rangeland, along with small farming villages and towns. Corn, wheat, hay, soybeans, and oats are all typical crops. Most villages and towns in this region boast both a water tower and a grain elevator. Irrigation water is available from both surface and subterranean sources. Surface water sources include the South Platte, the Arkansas River, and a few other streams. Subterranean water is generally accessed through artesian wells. Heavy usage of these wells for irrigation purposes caused underground water reserves to decline in the region. Eastern Colorado also hosts a considerable amount and range of livestock, such as cattle ranches and hog farms.[56]

Front Range

Roughly 70% of Colorado’s population resides along the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains in the Front Range Urban Corridor between Cheyenne, Wyoming, and Pueblo, Colorado. This region is partially protected from prevailing storms that blow in from the Pacific Ocean region by the high Rockies in the middle of Colorado. The “Front Range” includes Denver, Boulder, Fort Collins, Loveland, Castle Rock, Colorado Springs, Pueblo, Greeley, and other townships and municipalities in between. On the other side of the Rockies, the significant population centers in western Colorado (which is known as “The Western Slope”) are the cities of Grand Junction, Durango, and Montrose.[citation needed]

Mountains

To the west of the Great Plains of Colorado rises the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains. Notable peaks of the Rocky Mountains include Longs Peak, Mount Blue Sky, Pikes Peak, and the Spanish Peaks near Walsenburg, in southern Colorado. This area drains to the east and the southeast, ultimately either via the Mississippi River or the Rio Grande into the Gulf of Mexico.[citation needed]

The Rocky Mountains within Colorado contain 53 true peaks and 58 named peaks[57] that are 14,000 feet (4,267 m) or higher in elevation above sea level, known as fourteeners.[58] These mountains are largely covered with trees such as conifers and aspens up to the tree line, at an elevation of about 12,000 feet (3,658 m) in southern Colorado to about 10,500 feet (3,200 m) in northern Colorado. Above this tree line, only alpine vegetation grows.[citation needed]

Much of the alpine snow melts by mid-August except for a few snow-capped peaks and a few small glaciers. The Colorado Mineral Belt, stretching from the San Juan Mountains in the southwest to Boulder and Central City on the front range, contains most of the historic gold- and silver-mining districts of Colorado. The 30 highest major summits of the Rocky Mountains of North America are all within the state.[citation needed]

The summit of Mount Elbert at 14,437.6 feet (4,400.58 m) elevation in Lake County is the highest point in Colorado and the Rocky Mountains of North America.[7][59] Colorado is the only U.S. state that lies entirely above 1,000 meters elevation. The point where the Arikaree River flows out of Yuma County, Colorado, and into Cheyenne County, Kansas, is the lowest in Colorado at 3,317 feet (1,011 m) elevation. This point, which is the highest low elevation point of any state,[8][60] is higher than the high elevation points of 18 states and the District of Columbia.[citation needed]

Continental Divide

The Continental Divide of the Americas extends along the crest of the Rocky Mountains. The area of Colorado to the west of the Continental Divide is called the Western Slope of Colorado. West of the Continental Divide, water flows to the southwest via the Colorado River and the Green River towards the Gulf of California.[citation needed]

Within the interior of the Rocky Mountains are several large parks which are high broad basins. In the north, on the east side of the Continental Divide is the North Park of Colorado. The North Park is drained by the North Platte River, which flows north into Wyoming and Nebraska. Just to the south of North Park, but on the western side of the Continental Divide, is the Middle Park of Colorado, which is drained by the Colorado River. The South Park of Colorado is the region of the headwaters of the South Platte River.[citation needed]

South Central region

In south-central Colorado is the large San Luis Valley, where the headwaters of the Rio Grande are located. The northern part of the valley is the San Luis Closed Basin, an endorheic basin that helped created the Great Sand Dunes. The valley sits between the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and San Juan Mountains. The Rio Grande drains due south into New Mexico, Texas, and Mexico. Across the Sangre de Cristo Range to the east of the San Luis Valley lies the Wet Mountain Valley. These basins, particularly the San Luis Valley, lie along the Rio Grande rift, a major geological formation of the Rocky Mountains, and its branches.[citation needed]

Western Slope

The Western Slope of Colorado includes the western face of the Rocky Mountains and all of the area to the western border. This area includes several terrains and climates from alpine mountains to arid deserts. The Western Slope includes many ski resort towns in the Rocky Mountains and towns west to Utah. It is less populous than the Front Range but includes a large number of national parks and monuments.[citation needed]

The northwestern corner of Colorado is a sparsely populated region, and it contains part of the noted Dinosaur National Monument, which not only is a paleontological area, but is also a scenic area of rocky hills, canyons, arid desert, and streambeds. Here, the Green River briefly crosses over into Colorado.[citation needed]

The Western Slope of Colorado is drained by the Colorado River and its tributaries (primarily the Gunnison River, Green River, and the San Juan River). The Colorado River flows through Glenwood Canyon, and then through an arid valley made up of desert from Rifle to Parachute, through the desert canyon of De Beque Canyon, and into the arid desert of Grand Valley, where the city of Grand Junction is located.[citation needed]

Also prominent is the Grand Mesa, which lies to the southeast of Grand Junction; the high San Juan Mountains, a rugged mountain range; and to the north and west of the San Juan Mountains, the Colorado Plateau.[citation needed]

Grand Junction, Colorado, at the confluence of the Colorado and Gunnison Rivers, is the largest city on the Western Slope. Grand Junction and Durango are the only major centers of television broadcasting west of the Continental Divide in Colorado, though most mountain resort communities publish daily newspapers. Grand Junction is located at the juncture of Interstate 70 and US 50, the only major highways in western Colorado. Grand Junction is also along the major railroad of the Western Slope, the Union Pacific. This railroad also provides the tracks for Amtrak‘s California Zephyr passenger train, which crosses the Rocky Mountains between Denver and Grand Junction.[citation needed]

The Western Slope includes multiple notable destinations in the Colorado Rocky Mountains, including Glenwood Springs, with its resort hot springs, and the ski resorts of Aspen, Breckenridge, Vail, Crested Butte, Steamboat Springs, and Telluride.[citation needed]

Higher education in and near the Western Slope can be found at Colorado Mesa University in Grand Junction, Western Colorado University in Gunnison, Fort Lewis College in Durango, and Colorado Mountain College in Glenwood Springs and Steamboat Springs.[citation needed]

The Four Corners Monument in the southwest corner of Colorado marks the common boundary of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah; the only such place in the United States.[citation needed]

Climate

The climate of Colorado is more complex than states outside of the Mountain States region. Unlike most other states, southern Colorado is not always warmer than northern Colorado. Most of Colorado is made up of mountains, foothills, high plains, and desert lands. Mountains and surrounding valleys greatly affect the local climate. Northeast, east, and southeast Colorado are mostly the high plains, while Northern Colorado is a mix of high plains, foothills, and mountains. Northwest and west Colorado are predominantly mountainous, with some desert lands mixed in. Southwest and southern Colorado are a complex mixture of desert and mountain areas.[citation needed]

Eastern Plains

The climate of the Eastern Plains is semi-arid (Köppen climate classification: BSk) with low humidity and moderate precipitation, usually from 15 to 25 inches (380 to 640 mm) annually, although many areas near the rivers are semi-humid climate. The area is known for its abundant sunshine and cool, clear nights, which give this area a great average diurnal temperature range. The difference between the highs of the days and the lows of the nights can be considerable as warmth dissipates to space during clear nights, the heat radiation not being trapped by clouds. The Front Range urban corridor, where most of the population of Colorado resides, lies in a pronounced precipitation shadow as a result of being on the lee side of the Rocky Mountains.[61]

In summer, this area can have many days above 95 °F (35 °C) and often 100 °F (38 °C).[62] On the plains, the winter lows usually range from 25 to −10 °F (−4 to −23 °C). About 75% of the precipitation falls within the growing season, from April to September, but this area is very prone to droughts. Most of the precipitation comes from thunderstorms, which can be severe, and from major snowstorms that occur in the winter and early spring. Otherwise, winters tend to be mostly dry and cold.[63]

In much of the region, March is the snowiest month. April and May are normally the rainiest months, while April is the wettest month overall. The Front Range cities closer to the mountains tend to be warmer in the winter due to Chinook winds which warm the area, sometimes bringing temperatures of 70 °F (21 °C) or higher in the winter.[63] The average July temperature is 55 °F (13 °C) in the morning and 90 °F (32 °C) in the afternoon. The average January temperature is 18 °F (−8 °C) in the morning and 48 °F (9 °C) in the afternoon, although variation between consecutive days can be 40 °F (4 °C).[citation needed]

Front Range foothills

Just west of the plains and into the foothills, there is a wide variety of climate types. Locations merely a few miles apart can experience entirely different weather depending on the topography. Most valleys have a semi-arid climate, not unlike the eastern plains, which transitions to an alpine climate at the highest elevations. Microclimates also exist in local areas that run nearly the entire spectrum of climates, including subtropical highland (Cfb/Cwb), humid subtropical (Cfa), humid continental (Dfa/Dfb), Mediterranean (Csa/Csb) and subarctic (Dfc).[64]

Extreme weather

Extreme weather changes are common in Colorado, although a significant portion of the extreme weather occurs in the least populated areas of the state. Thunderstorms are common east of the Continental Divide in the spring and summer, yet are usually brief. Hail is a common sight in the mountains east of the Divide and across the eastern Plains, especially the northeast part of the state. Hail is the most commonly reported warm-season severe weather hazard, and occasionally causes human injuries, as well as significant property damage.[65] The eastern Plains are subject to some of the biggest hail storms in North America.[55] Notable examples are the severe hailstorms that hit Denver on July 11, 1990,[66] and May 8, 2017, the latter being the costliest ever in the state.[67]

The Eastern Plains are part of the extreme western portion of Tornado Alley; some damaging tornadoes in the Eastern Plains include the 1990 Limon F3 tornado and the 2008 Windsor EF3 tornado, which devastated a small town.[68] Portions of the eastern Plains see especially frequent tornadoes, both those spawned from mesocyclones in supercell thunderstorms and from less intense landspouts, such as within the Denver convergence vorticity zone (DCVZ).[65]

The Plains are also susceptible to occasional floods and particularly severe flash floods, which are caused both by thunderstorms and by the rapid melting of snow in the mountains during warm weather. Notable examples include the 1965 Denver Flood,[69] the Big Thompson River flooding of 1976 and the 2013 Colorado floods. Hot weather is common during summers in Denver. The city’s record in 1901 for the number of consecutive days above 90 °F (32 °C) was broken during the summer of 2008. The new record of 24 consecutive days surpassed the previous record by almost a week.[70]

Much of Colorado is very dry, with the state averaging only 17 inches (430 mm) of precipitation per year statewide. The state rarely experiences a time when some portion is not in some degree of drought.[71] The lack of precipitation contributes to the severity of wildfires in the state, such as the Hayman Fire of 2002. Other notable fires include the Fourmile Canyon Fire of 2010, the Waldo Canyon Fire and High Park Fire of June 2012, and the Black Forest Fire of June 2013. Even these fires were exceeded in severity by the Pine Gulch Fire, Cameron Peak Fire, and East Troublesome Fire in 2020, all being the three largest fires in Colorado history (see 2020 Colorado wildfires). And the Marshall Fire which started on December 30, 2021, while not the largest in state history, was the most destructive ever in terms of property loss (see Marshall Fire).[citation needed]

However, some of the mountainous regions of Colorado receive a huge amount of moisture from winter snowfalls. The spring melts of these snows often cause great waterflows in the Yampa River, the Colorado River, the Rio Grande, the Arkansas River, the North Platte River, and the South Platte River.[citation needed]

Water flowing out of the Colorado Rocky Mountains is a very significant source of water for the farms, towns, and cities of the southwest states of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Nevada, as well as the Midwest, such as Nebraska and Kansas, and the southern states of Oklahoma and Texas. A significant amount of water is also diverted for use in California; occasionally (formerly naturally and consistently), the flow of water reaches northern Mexico.[citation needed]

Climate change

Climate change in Colorado encompasses the effects of climate change, attributed to man-made increases in atmospheric greenhouse gases, in the U.S. state of Colorado.

In 2019 The Denver Post reported that “[i]ndividuals living in southeastern Colorado are more vulnerable to potential health effects from climate change than residents in other parts of the state”.[72] The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has more broadly reported:

“Colorado’s climate is changing. Most of the state has warmed one or two degrees (F) in the last century. Throughout the western United States, heat waves are becoming more common, snow is melting earlier in spring, and less water flows through the Colorado River.[73][74] Rising temperatures[75] and recent droughts[76] in the region have killed many trees by drying out soils, increasing the risk of forest fires, or enabling outbreaks of forest insects. In the coming decades, the changing climate is likely to decrease water availability and agricultural yields in Colorado, and further increase the risk of wildfires“.[77]

Records

The highest official ambient air temperature ever recorded in Colorado was 115 °F (46.1 °C) on July 20, 2019, at John Martin Dam. The lowest official air temperature was −61 °F (−51.7 °C) on February 1, 1985, at Maybell.[78][79]

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alamosa | 34/−2 2/−19 | 40/6 4/−14 | 50/17 10/−8 | 59/24 15/−4 | 69/33 21/1 | 79/41 26/5 | 82/47 28/8 | 80/46 27/8 | 73/40 23/4 | 62/25 17/−4 | 47/12 8/−11 | 35/1 2/−17 |

| Colorado Springs | 43/18 6/−8 | 45/20 7/−7 | 52/26 11/−3 | 60/33 16/1 | 69/43 21/6 | 79/51 26/11 | 85/57 29/14 | 82/56 28/13 | 75/47 24/8 | 63/36 17/2 | 51/25 11/−4 | 42/18 6/−8 |

| Denver | 49/20 9/−7 | 49/21 9/−6 | 56/29 13/−2 | 64/35 18/2 | 73/46 23/8 | 84/54 29/12 | 92/61 33/16 | 89/60 32/16 | 81/50 27/10 | 68/37 20/3 | 55/26 13/−3 | 47/18 8/−8 |

| Grand Junction | 38/17 3/−8 | 45/24 7/−4 | 57/31 14/-1 | 65/38 18/3 | 76/47 24/8 | 88/56 31/13 | 93/63 34/17 | 90/61 32/16 | 80/52 27/11 | 66/40 19/4 | 51/28 11/−2 | 39/19 4/−7 |

| Pueblo | 47/14 8/−10 | 51/17 11/−8 | 59/26 15/−3 | 67/34 19/1 | 77/44 25/7 | 87/53 31/12 | 93/59 34/15 | 90/58 32/14 | 82/48 28/9 | 69/34 21/1 | 56/23 13/−5 | 46/14 8/−10 |

Extreme temperatures

| Climate data for Colorado | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 84 (29) | 88 (31) | 96 (36) | 100 (38) | 107 (42) | 114 (46) | 115 (46) | 112 (44) | 108 (42) | 100 (38) | 90 (32) | 88 (31) | 115 (46) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −56 (−49) | −61 (−52) | −44 (−42) | −30 (−34) | −11 (−24) | 10 (−12) | 18 (−8) | 15 (−9) | −2 (−19) | −28 (−33) | −37 (−38) | −50 (−46) | −61 (−52) |

| Source: Colorado Climate Center[81] | |||||||||||||

Earthquakes

Despite its mountainous terrain, Colorado experiences less seismic activity than states like California and Alaska. There are over 90 potentially active faults, and since 1867, Colorado has experienced 700 recorded earthquakes of magnitude 2.5 or higher.[82] The U.S. National Earthquake Information Center is located in Golden.[83]

On August 22, 2011, a 5.3 magnitude earthquake occurred 9 miles (14 km) west-southwest of the city of Trinidad.[84] There were no casualties and only a small amount of damage was reported. It was the second-largest earthquake in Colorado’s history, the largest being a magnitude 6.6 earthquake, recorded in 1882.[85] Four minor earthquakes rattled Colorado on August 24, 2018, ranging from magnitude 2.9 to 4.3.[86] As of June 2020, there were 525 recorded earthquakes in Colorado since 1973, a majority of which range 2 to 3.5 on the Richter scale.[87]

Fauna

A process of extirpation by trapping and poisoning of the gray wolf (Canis lupus) from Colorado in the 1930s saw the last wild wolf in the state shot in 1945.[88] A wolf pack recolonized Moffat County, Colorado in northwestern Colorado in 2019.[89] Cattle farmers have expressed concern that a returning wolf population potentially threatens their herds.[88] Coloradans voted to reintroduce gray wolves in 2020, with the state committing to a plan to have a population in the state by 2022 and permitting non-lethal methods of driving off wolves attacking livestock and pets.[90][91]

While there is fossil evidence of Harrington’s mountain goat in Colorado between at least 800,000 years ago and its extinction with megafauna roughly 11,000 years ago, the mountain goat is not native to Colorado but was instead introduced to the state over time during the interval between 1947 and 1972. Despite being an artificially-introduced species, the state declared mountain goats a native species in 1993.[92] In 2013, 2014, and 2019, an unknown illness killed nearly all mountain goat kids, leading to a Colorado Parks and Wildlife investigation.[93][94]

The native population of pronghorn in Colorado has varied wildly over the last century, reaching a low of only 15,000 individuals during the 1960s. However, conservation efforts succeeded in bringing the stable population back up to roughly 66,000 by 2013.[95] The population was estimated to have reached 85,000 by 2019 and had increasingly more run-ins with the increased suburban housing along the eastern Front Range. State wildlife officials suggested that landowners would need to modify fencing to allow the greater number of pronghorns to move unabated through the newly developed land.[96] Pronghorns are most readily found in the northern and eastern portions of the state, with some populations also in the western San Juan Mountains.[97]

Common wildlife found in the mountains of Colorado include mule deer, southwestern red squirrel, golden-mantled ground squirrel, yellow-bellied marmot, moose, American pika, and red fox, all at exceptionally high numbers, though moose are not native to the state.[98][99][100][101] The foothills include deer, fox squirrel, desert cottontail, mountain cottontail, and coyote.[102][103] The prairies are home to black-tailed prairie dog, the endangered swift fox, American badger, and white-tailed jackrabbit.[104][105][106]

Government

State government

| Office | Name | Party |

|---|---|---|

| Governor | Jared Polis | Democratic |

| Lieutenant Governor | Dianne Primavera | Democratic |

| Secretary of State | Jena Griswold | Democratic |

| Attorney General | Phil Weiser | Democratic |

| Treasurer | Dave Young | Democratic |

Like the federal government and all other U.S. states, Colorado’s state constitution provides for three branches of government: the legislative, the executive, and the judicial branches.[citation needed][107]

The Governor of Colorado heads the state’s executive branch. The current governor is Jared Polis, a Democrat. Colorado’s other statewide elected executive officers are the Lieutenant Governor of Colorado (elected on a ticket with the Governor), Secretary of State of Colorado, Colorado State Treasurer, and Attorney General of Colorado, all of whom serve four-year terms.[citation needed]

The seven-member Colorado Supreme Court is the state’s highest court. The Colorado Court of Appeals, with 22 judges, sits in divisions of three judges each. Colorado is divided into 23 judicial districts, each of which has a district court and a county court with limited jurisdiction. The state also has specialized water courts, which sit in seven distinct divisions around the state and which decide matters relating to water rights and the use and administration of water.[citation needed]

The state legislative body is the Colorado General Assembly, which is made up of two houses – the House of Representatives and the Senate. The House has 65 members and the Senate has 35. As of 2023, the Democratic Party holds a 23 to 12 majority in the Senate and a 46 to 19 majority in the House.[citation needed]

Most Coloradans are native to other states (nearly 60% according to the 2000 census),[108] and this is illustrated by the fact that the state did not have a native-born governor from 1975 (when John David Vanderhoof left office) until 2007, when Bill Ritter took office; his election the previous year marked the first electoral victory for a native-born Coloradan in a gubernatorial race since 1958 (Vanderhoof had ascended from the Lieutenant Governorship when John Arthur Love was given a position in Richard Nixon‘s administration in 1973).[citation needed]

Tax is collected by the Colorado Department of Revenue.[citation needed]

Politics

| Party | Number of voters | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unaffiliated | 2,011,247 | 49.20% | |

| Democratic | 1,039,477 | 25.43% | |

| Republican | 940,271 | 23.00% | |

| Libertarian | 37,166 | 0.91% | |

| No Labels | 26,843 | 0.65% | |

| American Constitution | 11,725 | 0.29% | |

| Green | 8,635 | 0.21% | |

| Approval Voting | 5,067 | 0.12% | |

| Unity | 4,087 | 0.10% | |

| Center | 3,674 | 0.09% | |

| Total | 4,087,582 | 100.00% | |

Colorado was once considered a swing state, but has become a relatively safe blue state in both state and federal elections since the late 2010s. In presidential elections, it had not been won until 2020 by double digits since 1984 and has backed the winning candidate in 9 of the last 11 elections. Coloradans have elected 17 Democrats and 12 Republicans to the governorship in the last 100 years.[citation needed]

In presidential politics, Colorado was considered a reliably Republican state during the post-World War II era, voting for the Democratic candidate only in 1948, 1964, and 1992. However, it became a competitive swing state in the 1990s. Since the mid-2000s, it has swung heavily to the Democrats, voting for Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012, Hillary Clinton in 2016, Joe Biden in 2020, and Kamala Harris in 2024.[citation needed]

Colorado politics exhibits a contrast between conservative cities such as Colorado Springs and Grand Junction, and liberal cities such as Boulder and Denver. Democrats are strongest in metropolitan Denver, the college towns of Fort Collins and Boulder, southern Colorado (including Pueblo), and several western ski resort counties. The Republicans are strongest in the Eastern Plains, Colorado Springs, Greeley, and far Western Colorado near Grand Junction.[citation needed]

Colorado is represented by two members of the United States Senate:[citation needed]

- Class 2, John Hickenlooper (Democratic), since 2021

- Class 3, Michael Bennet (Democratic), since 2009

Colorado is represented by eight members of the United States House of Representatives:[citation needed]

- 1st district: Diana DeGette (Democratic), since 1997

- 2nd district: Joe Neguse (Democratic), since 2019

- 3rd district: Jeff Hurd (Republican), since 2025

- 4th district: Lauren Boebert (Republican), since 2025 (3rd district 2021-2025)

- 5th district: Jeff Crank (Republican), since 2025

- 6th district: Jason Crow (Democratic), since 2019

- 7th district: Brittany Pettersen (Democratic), since 2023

- 8th district: Gabe Evans (Republican), since 2025

In a 2020 study, Colorado was ranked as the seventh easiest state for citizens to vote in.[110]

Significant initiatives and legislation enacted in Colorado

Colorado was the first state in the union to enact, by voter referendum, a law extending suffrage to women. That initiative was approved by the state’s voters on November 7, 1893.[111]

On the November 8, 1932, ballot, Colorado approved the repeal of alcohol prohibition more than a year before the Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified.[citation needed]

Colorado has banned, via C.R.S. section 12-6-302, the sale of motor vehicles on Sunday since at least 1953.[112]

In 1972, Colorado voters rejected a referendum proposal to fund the 1976 Winter Olympics, which had been scheduled to be held in the state. Denver had been chosen by the International Olympic Committee as the host city on May 12, 1970.[113]

In 1992, by a margin of 53 to 47 percent, Colorado voters approved an amendment to the state constitution (Amendment 2) that would have prevented any city, town, or county in the state from taking any legislative, executive, or judicial action to recognize homosexuals or bisexuals as a protected class.[114] In 1996, in a 6–3 ruling in Romer v. Evans, the U.S. Supreme Court found that preventing protected status based upon homosexuality or bisexuality did not satisfy the Equal Protection Clause.[115]

In 2006, voters passed Amendment 43, which banned same-sex marriage in Colorado.[116] That initiative was nullified by the U.S. Supreme Court‘s 2015 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges. In 2024, Colorado residents voted to establish an explicit right to abortion in Colorado‘s state constitution[117][118] and to repeal Amendment 43’s defunct marriage ban.[119][120]

In 2012, voters amended the state constitution protecting the “personal use” of marijuana for adults, establishing a framework to regulate cannabis like alcohol. The first recreational marijuana shops in Colorado, and by extension the United States, opened their doors on January 1, 2014.[121]

On October 30, 2019, Colorado became the first state to accept digital ID via its myColorado app.[122] The state-issued digital identifications will be considered valid when Real ID enforcement begins in 2025, in line with the Real ID Act of 2005. By November 2022 The Colorado Governor’s Office of Information Technology announced that the myColorado app had over 1 million users.[123]

On December 19, 2023, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that Donald Trump was disqualified from the 2024 United States presidential election in part due to his alleged incitement of the January 6 United States Capitol attack.[124] On March 4, 2024, the United States Supreme Court overruled the Colorado decision.[125]

Counties

The 64 counties of the U.S. State of Colorado

The State of Colorado is divided into 64 counties. Two of these counties, the City and County of Broomfield and the City and County of Denver, have consolidated city and county governments. Counties are important units of government in Colorado since there are no civil townships or other minor civil divisions.[citation needed]

The most populous county in Colorado is El Paso County, the home of the City of Colorado Springs. The second most populous county is the City and County of Denver, the state capital. Five of the 64 counties now have more than 500,000 residents, while 12 have fewer than 5,000 residents. The ten most populous Colorado counties are all located in the Front Range Urban Corridor. Mesa County is the most populous county on the Colorado Western Slope. The least populous Colorado county is Hinsdale County with 747 residents.[d]

| 2024 rank[d] | County | County seat | Most populous city | 2024 population[d] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | El Paso County | Colorado Springs | Colorado Springs | 752,772 |

| 2 | City and County of Denver[e] | 729,019 | ||

| 3 | Arapahoe County | Littleton[f] | Aurora[g] | 666,918 |

| 4 | Jefferson County | Golden | Lakewood | 578,533 |

| 5 | Adams County | Brighton[h] | Thornton[i] | 542,973 |

| 6 | Douglas County | Castle Rock | Highlands Ranch[j] | 393,995 |

| 7 | Larimer County | Fort Collins | Fort Collins | 374,574 |

| 8 | Weld County | Greeley | Greeley | 369,745 |

| 9 | Boulder County | Boulder | Boulder | 330,262 |

| 10 | Pueblo County | Pueblo | Pueblo | 169,866 |

| 11 | Mesa County | Grand Junction | Grand Junction | 161,260 |

| 12 | City and County of Broomfield[k] | 78,323 | ||

| 13 | Garfield County | Glenwood Springs | Rifle | 63,167 |

| 14 | La Plata County | Durango | Durango | 56,823 |

| 15 | Eagle County | Eagle | Edwards[l] | 54,330 |

| 16 | Fremont County | Cañon City | Cañon City | 50,093 |

Municipalities

Colorado has 273 active incorporated municipalities, comprising 198 towns, 73 cities, and two consolidated city and county governments.[127][128] At the 2020 United States census, 4,299,942 of the 5,773,714 Colorado residents (74.47%) lived in one of these municipalities. Another 714,417 residents (12.37%) lived in one of the 210 census-designated places, while the remaining 759,355 residents (13.15%) lived in the many rural and mountainous areas of the state.[126]

Colorado municipalities operate under one of five types of municipal governing authority. Colorado currently has two consolidated city and county governments, 61 home rule cities, 12 statutory cities, 35 home rule towns, 161 statutory towns, and one territorial charter municipality.[citation needed]

The most populous municipality is the City and County of Denver. Colorado has 12 municipalities with more than 100,000 residents, and 17 with fewer than 100 residents. The 16 most populous Colorado municipalities are all located in the Front Range Urban Corridor. The City of Grand Junction is the most populous municipality on the Colorado Western Slope. The Town of Carbonate has had no year-round population since the 1890 census due to its severe winter weather and difficult access.[m]

Unincorporated communities

In addition to its 272 municipalities, Colorado has 210 unincorporated census-designated places (CDPs) and many other small communities. The most populous unincorporated community in Colorado is Highlands Ranch south of Denver. The seven most populous CDPs are located in the Front Range Urban Corridor. The Clifton CDP is the most populous CDP on the Colorado Western Slope.[130]

| 2020 rank[126] | Census-designated place | County | 2020 census[126] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Highlands Ranch CDP | Douglas County | 103,444 |

| 2 | Security-Widefield CDP | El Paso County | 38,639 |

| 3 | Dakota Ridge CDP | Jefferson County | 33,892 |

| 4 | Ken Caryl CDP | Jefferson County | 33,811 |

| 5 | Pueblo West CDP | Pueblo County | 33,086 |

| 6 | Columbine CDP | Jefferson and Arapahoe counties | 25,229 |

| 7 | Four Square Mile CDP | Arapahoe County | 22,872 |

| 8 | Clifton CDP | Mesa County | 20,413 |

| 9 | Cimarron Hills CDP | El Paso County | 19,311 |

| 10 | Sherrelwood CDP | Adams County | 19,228 |

Special districts

Colorado has more than 4,000 special districts, most with property tax authority. These districts may provide health services, ambulance, schools, law enforcement, fire protection, water, sewage, drainage, irrigation, transportation, recreation, infrastructure, cultural facilities, business support, redevelopment, or other services[131].

Some of these districts have the authority to levy sales tax as well as property tax and use fees.

Some of the more notable Colorado districts are:

- The Regional Transportation District (RTD), which affects the counties of Denver, Boulder, Jefferson, and portions of Adams, Arapahoe, Broomfield, and Douglas Counties

- The Scientific and Cultural Facilities District (SCFD) that provides funding for cultural programing in Adams, Arapahoe, Boulder, Broomfield, Denver, Douglas, and Jefferson Counties

- The Football Stadium District (FD or FTBL), approved by the voters to pay for and help build the Denver Broncos‘ stadium Empower Field at Mile High.

- Local Improvement Districts (LID) within designated areas of Jefferson and Broomfield counties.

- The Metropolitan Major League Baseball Stadium District, approved by voters to pay for and help build the Colorado Rockies‘ stadium Coors Field.

- Regional Transportation Authority (RTA) taxes at varying rates in Basalt, Carbondale, Glenwood Springs, and Gunnison County.

Statistical areas

The 17 core-based statistical areas in the U.S. State of Colorado.

Most recently on July 21, 2023, the Office of Management and Budget defined 21 statistical areas for Colorado comprising four combined statistical areas, seven metropolitan statistical areas, and ten micropolitan statistical areas.[132]

The most populous of the seven metropolitan statistical areas in Colorado is the 10-county Denver–Aurora–Centennial, CO Metropolitan Statistical Area with a population of 2,963,821 at the 2020 United States census, an increase of +15.29% since the 2010 census.[126]

The more extensive 12-county Denver–Aurora–Greeley, CO Combined Statistical Area had a population of 3,623,560 at the 2020 census, an increase of +17.23% since the 2010 census.[126]

The most populous extended metropolitan region in Rocky Mountain Region is the 18-county Front Range Urban Corridor along the northeast face of the Southern Rocky Mountains. This region with Denver at its center had a population of 5,055,344 at the 2020 census, an increase of +16.65% since the 2010 census.[126]

Demographics

The United States Census Bureau estimated the population of Colorado on July 1, 2024, at 5,957,493, a 3.2% increase since the 2020 United States census.[126]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 34,277 | — | |

| 1870 | 39,864 | 16.3% | |

| 1880 | 194,327 | 387.5% | |

| 1890 | 413,249 | 112.7% | |

| 1900 | 539,700 | 30.6% | |

| 1910 | 799,024 | 48.0% | |

| 1920 | 939,629 | 17.6% | |

| 1930 | 1,035,791 | 10.2% | |

| 1940 | 1,123,296 | 8.4% | |

| 1950 | 1,325,089 | 18.0% | |

| 1960 | 1,753,947 | 32.4% | |

| 1970 | 2,207,259 | 25.8% | |

| 1980 | 2,889,964 | 30.9% | |

| 1990 | 3,294,394 | 14.0% | |

| 2000 | 4,301,262 | 30.6% | |

| 2010 | 5,029,196 | 16.9% | |

| 2020 | 5,773,714 | 14.8% | |

| 2025 (est.) | 6,012,561 | [133] | 4.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census | |||

| Race and ethnicity[134] | Non-Hispanic | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 65.1% | 69.4% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[n] | — | 21.9% | ||

| Black | 3.8% | 4.9% | ||

| Asian | 3.4% | 4.7% | ||

| Native American | 0.6% | 2.1% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0.2% | 0.4% | ||

| Other | 0.5% | 1.5% | ||

| Racial composition | 1970[135] | 1990[135] | 2000[136] | 2010[137] | 2020[138] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (includes White Hispanics) | 95.7% | 88.2% | 82.8% | 81.3% | 70.7% |

| Black | 3.0% | 4.0% | 3.8% | 4.0% | 4.1% |

| Asian | 0.5% | 1.8% | 2.2% | 2.8% | 3.5% |

| Native | 0.4% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 1.1% | 1.3% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | – | – | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| Other race | 0.4% | 5.1% | 7.2% | 7.2% | 8.0% |

| Two or more races | – | – | 2.8% | 3.4% | 12.3% |

Non-Hispanic White 40–50%50–60%60–70%70–80%80–90%Hispanic or Latino 40–50%50–60%

Coloradan Hispanics and Latinos (of any race and heritage) made up 20.7% of the population.[139] According to the 2000 census, the largest ancestry groups in Colorado are German (22%), Mexican (18%), Irish (12%), and English (12%). Persons reporting German ancestry are especially numerous in the Front Range, the Rockies (west-central counties), and Eastern parts/High Plains.[citation needed]

Colorado has a high proportion of Hispanic, mostly Mexican-American, citizens in Metropolitan Denver, Colorado Springs, as well as the smaller cities of Greeley and Pueblo, and elsewhere. Southern, Southwestern, and Southeastern Colorado have a large number of Hispanos, the descendants of the early settlers of colonial Spanish origin. In 1940, the U.S. Census Bureau reported Colorado’s population as 8.2% Hispanic and 90.3% non-Hispanic White.[140] The Hispanic population of Colorado has continued to grow quickly over the past decades. By 2019, Hispanics made up 22% of Colorado’s population, and Non-Hispanic Whites made up 70%.[141] Spoken English in Colorado has many Spanish idioms.[142]

Colorado also has some large African-American communities located in Denver, in the neighborhoods of Montbello, Five Points, Whittier, and many other East Denver areas. The state has sizable numbers of Asian-Americans of Mongolian, Chinese, Filipino, Korean, Southeast Asian, and Japanese descent. The highest population of Asian Americans can be found on the south and southeast side of Denver, as well as some on Denver’s southwest side. The Denver metropolitan area is considered more liberal and diverse than much of the state when it comes to political issues and environmental concerns.[citation needed]

The population of Native Americans in the state is small. Native Americans are concentrated in metropolitan Denver and the southwestern corner of Colorado, where there are two Ute reservations.[143]

The majority of Colorado’s immigrants are from Mexico, India, China, Vietnam, Korea, Germany and Canada.[144]

There were a total of 70,331 births in Colorado in 2006. (Birth rate of 14.6 per thousand.) In 2007, non-Hispanic Whites were involved in 59.1% of all births.[145] Some 14.06% of those births involved a non-Hispanic White person and someone of a different race, most often with a couple including one Hispanic. A birth where at least one Hispanic person was involved counted for 43% of the births in Colorado.[146] As of the 2010 census, Colorado has the seventh highest percentage of Hispanics (20.7%) in the U.S. behind New Mexico (46.3%), California (37.6%), Texas (37.6%), Arizona (29.6%), Nevada (26.5%), and Florida (22.5%). Per the 2000 census, the Hispanic population is estimated to be 918,899, or approximately 20% of the state’s total population. Colorado has the 5th-largest population of Mexican-Americans, behind California, Texas, Arizona, and Illinois. In percentages, Colorado has the 6th-highest percentage of Mexican-Americans, behind New Mexico, California, Texas, Arizona, and Nevada.[147]

Birth data

In 2011, 46% of Colorado’s population younger than the age of one were minorities, meaning that they had at least one parent who was not non-Hispanic White.[148][149]

Note: Births in table do not add up, because Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

| Race | 2013[150] | 2014[151] | 2015[152] | 2016[153] | 2017[154] | 2018[155] | 2019[156] | 2020[157] | 2021[158] | 2022[159] | 2023[160] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 39,872 (61.3%) | 40,629 (61.7%) | 40,878 (61.4%) | 39,617 (59.5%) | 37,516 (58.3%) | 36,466 (58.0%) | 36,022 (57.3%) | 34,924 (56.8%) | 36,334 (57.7%) | 35,076 (56.2%) | 33,640 (54.7%) |

| Black | 3,760 (5.8%) | 3,926 (6.0%) | 4,049 (6.1%) | 3,004 (4.5%) | 3,110 (4.8%) | 3,032 (4.8%) | 3,044 (4.8%) | 3,146 (5.1%) | 2,988 (4.7%) | 2,981 (4.8%) | 2,904 (4.7%) |

| Asian | 2,863 (4.4%) | 3,010 (4.6%) | 2,973 (4.5%) | 2,617 (3.9%) | 2,611 (4.1%) | 2,496 (4.0%) | 2,540 (4.0%) | 2,519 (4.1%) | 2,490 (4.0%) | 2,450 (3.9%) | 2,498 (4.1%) |

| American Indian | 793 (1.2%) | 777 (1.2%) | 803 (1.2%) | 412 (0.6%) | 421 (0.7%) | 352 (0.6%) | 365 (0.6%) | 338 (0.5%) | 323 (0.5%) | 336 (0.5%) | 310 (0.5%) |

| Pacific Islander | … | … | … | 145 (0.2%) | 145 (0.2%) | 155 (0.2%) | 168 (0.3%) | 169 (0.3%) | 202 (0.3%) | 203 (0.3%) | 256 (0.4%) |

| Hispanic (any race) | 17,821 (27.4%) | 17,665 (26.8%) | 18,139 (27.2%) | 18,513 (27.8%) | 18,125 (28.2%) | 17,817 (28.3%) | 18,205 (29.0%) | 18,111 (29.4%) | 18,362 (29.2%) | 18,982 (30.4%) | 19,544 (31.8%) |

| Total | 65,007 (100%) | 65,830 (100%) | 66,581 (100%) | 66,613 (100%) | 64,382 (100%) | 62,885 (100%) | 62,869 (100%) | 61,494 (100%) | 62,949 (100%) | 62,383 (100%) | 61,494 (100%) |

- Since 2016, data for births of White Hispanic origin are not collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.[citation needed]

In 2017, Colorado recorded the second-lowest fertility rate in the United States outside of New England, after Oregon, at 1.63 children per woman.[154] Significant contributing factors to the decline in pregnancies were the Title X Family Planning Program and an intrauterine device grant from Warren Buffett‘s family.[161][162]

Language

English, the official language of the state, is the most commonly spoken language in Colorado.[citation needed] The second most commonly spoken language in the state is Spanish.[163] The Colorado River Numic language, also known as the Ute dialect, is still spoken in Colorado.[citation needed]

Religion

- Protestantism 39 (38.2%)

- Catholicism 19 (18.6%)

- Mormonism 2 (1.96%)

- Eastern Orthodoxy 1 (0.98%)

- Unitarianism/Unitarian 1 (0.98%)

- Judaism 1 (0.98%)

- New Age 2 (1.96%)

- East Asian Religions 2 (1.96%)

- Hinduism 1 (0.98%)

- No religion 34 (33.3%)

Major religious affiliations of the people of Colorado as of 2014 were 64% Christian, of whom there are 44% Protestant, 16% Roman Catholic, 3% Mormon, and 1% Eastern Orthodox.[165] Other religious breakdowns according to the Pew Research Center were 1% Judaism, 1% Muslim, 1% Buddhist, and 4% other. Secular Coloradans made up 29% of the population.[166] In 2020, according to the Public Religion Research Institute, Christianity was 66% of the population. Judaism was also reported to have increased in this separate study, forming 2% of the religious landscape, while the religiously unaffiliated were reported to form 28% of the population in this separate study.[167] In 2022, the same organization reported 61% was Christian (39% Protestant, 19% Catholic, 2% Mormon, 1% Eastern Orthodox), 2% New Age, 1% Jewish, 1% Hindu, and 34% religiously unaffiliated.[citation needed]

According to the Association of Religion Data Archives, the largest Christian denominations by the number of adherents in 2010 were the Catholic Church with 811,630; multi-denominational Evangelical Protestants with 229,981; and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 151,433.[168] In 2020, the Association of Religion Data Archives determined the largest Christian denominations were Catholics (873,236), non/multi/inter-denominational Protestants (406,798), and Mormons (150,509).[169] Throughout its non-Christian population, there were 12,500 Hindus, 7,101 Hindu Yogis, and 17,369 Buddhists at the 2020 study.[citation needed]

Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church was the first permanent Catholic parish in modern-day Colorado and was constructed by Spanish colonists from New Mexico in modern-day Conejos.[170] Latin Church Catholics are served by three dioceses: the Archdiocese of Denver and the Dioceses of Colorado Springs and Pueblo.[citation needed]

The first permanent settlement by members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Colorado arrived from Mississippi and initially camped along the Arkansas River just east of the present-day site of Pueblo.[171]

Health

Colorado is generally considered among the healthiest states by behavioral and healthcare researchers. Among the positive contributing factors is the state’s well-known outdoor recreation opportunities and initiatives.[172] However, there is a stratification of health metrics with wealthier counties such as Douglas and Pitkin performing significantly better relative to southern, less wealthy counties such as Huerfano and Las Animas.[16]

Obesity

According to several studies, Coloradans have the lowest rates of obesity of any state in the US.[173] As of 2018, 24% of the population was considered medically obese, and while the lowest in the nation, the percentage had increased from 17% in 2004.[174][175]

Life expectancy

According to a report in the Journal of the American Medical Association, residents of Colorado had a 2014 life expectancy of 80.21 years, the longest of any U.S. state.[176]

Homelessness

According to HUD‘s 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 10,397 homeless people in Colorado.[177][178]

Economy

In 2019 the total employment was 2,473,192. The number of employer establishments is 174,258.[179]

The Colorado GDP in 2024 was $553,323,000,000.[180] Median Annual Household Income in 2016 was $70,666, 8th in the nation.[181] Per capita personal income in 2010 was $51,940, ranking Colorado 11th in the nation.[182] The state’s economy broadened from its mid-19th-century roots in mining when irrigated agriculture developed, and by the late 19th century, raising livestock had become important. Early industry was based on the extraction and processing of minerals and agricultural products. Current agricultural products are cattle, wheat, dairy products, corn, and hay. In 2025, small businesses made up 99.5% of Colorado businesses, and employed 48.6% of the state’s work force.[183]

The federal government operates several federal facilities in the state, including NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense Command), United States Air Force Academy, Schriever Air Force Base located approximately 10 miles (16 kilometers) east of Peterson Air Force Base, and Fort Carson, both located in Colorado Springs within El Paso County; NOAA, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in Golden, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder; U.S. Geological Survey and other government agencies at the Denver Federal Center near Lakewood; the Denver Mint, Buckley Space Force Base, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the Byron G. Rogers Federal Building and United States Courthouse in Denver; and a federal Supermax Prison and other federal prisons near Cañon City. In addition to these and other federal agencies, Colorado has abundant National Forest land and four National Parks that contribute to federal ownership of 24,615,788 acres (99,617 km2) of land in Colorado, or 37% of the total area of the state.[184]

In the second half of the 20th century, the industrial and service sectors expanded greatly. The state’s economy is diversified and is notable for its concentration on scientific research and high-technology industries. Other industries include food processing, transportation equipment, machinery, chemical products, the extraction of metals such as gold (see Gold mining in Colorado), silver, and molybdenum. Colorado now also has the largest annual production of beer in any state.[185] Denver is an important financial center.

The state’s diverse geography and majestic mountains attract millions of tourists every year, including 85.2 million in 2018. Tourism contributes greatly to Colorado’s economy, with tourists generating $22.3 billion in 2018.[186]

Several nationally known brand names have originated in Colorado factories and laboratories. From Denver came the forerunner of telecommunications giant Qwest in 1879, Samsonite luggage in 1910, Gates belts and hoses in 1911, and Russell Stover Candies in 1923. Kuner canned vegetables began in Brighton in 1864. From Golden came Coors beer in 1873, CoorsTek industrial ceramics in 1920, and Jolly Rancher candy in 1949. CF&I railroad rails, wire, nails, and pipe debuted in Pueblo in 1892. Holly Sugar was first milled from beets in Holly in 1905, and later moved its headquarters to Colorado Springs. The present-day Swift packed meat of Greeley evolved from Monfort of Colorado, Inc., established in 1930. Estes model rockets were launched in Penrose in 1958. Fort Collins has been the home of Woodward Governor Company‘s motor controllers (governors) since 1870, and Waterpik dental water jets and showerheads since 1962. Celestial Seasonings herbal teas have been made in Boulder since 1969. Rocky Mountain Chocolate Factory made its first candy in Durango in 1981.[citation needed]

Colorado has a flat 4.63% income tax, regardless of income level. On November 3, 2020, voters authorized an initiative to lower that income tax rate to 4.55 percent. Unlike most states, which calculate taxes based on federal adjusted gross income, Colorado taxes are based on taxable income—income after federal exemptions and federal itemized (or standard) deductions.[187][188] Colorado’s state sales tax is 2.9% on retail sales. When state revenues exceed state constitutional limits, according to Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights legislation, full-year Colorado residents can claim a sales tax refund on their individual state income tax return. Many counties and cities charge their own rates, in addition to the base state rate. There are also certain county and special district taxes that may apply.[citation needed]

Real estate and personal business property are taxable in Colorado. The state’s senior property tax exemption was temporarily suspended by the Colorado Legislature in 2003. The tax break was scheduled to return for the assessment year 2006, payable in 2007.[citation needed]

As of May 2025, the state’s unemployment rate was 4.8%.[189]

The West Virginia teachers’ strike in 2018 inspired teachers in other states, including Colorado, to take similar action.[190]

Agriculture

Corn is grown in the Eastern Plains of Colorado. Arid conditions and drought negatively impacted yields in 2020 and 2022.[191]

Natural resources

Colorado has significant hydrocarbon resources. According to the Energy Information Administration, Colorado hosts seven of the largest natural gas fields in the United States, and two of the largest oil fields. Conventional and unconventional natural gas output from several Colorado basins typically accounts for more than five percent of annual U.S. natural gas production. Colorado’s oil shale deposits hold an estimated 1 trillion barrels (160 km3) of oil—nearly as much oil as the entire world’s proven oil reserves.[192] Substantial deposits of bituminous, subbituminous, and lignite coal are found in the state.[citation needed]

Uranium mining in Colorado goes back to 1872, when pitchblende ore was taken from gold mines near Central City, Colorado. Not counting byproduct uranium from phosphate, Colorado is considered to have the third-largest uranium reserves of any U.S. state, behind Wyoming and New Mexico. When Colorado and Utah dominated radium mining from 1910 to 1922, uranium and vanadium were the byproducts (giving towns like present-day Superfund site Uravan their names).[193] Uranium price increases from 2001 to 2007 prompted several companies to revive uranium mining in Colorado. During the 1940s certain communities–including Naturita and Paradox–earned the moniker of “yellowcake towns” from their relationship with uranium mining. Price drops and financing problems in late 2008 forced these companies to cancel or scale back the uranium-mining project. As of 2016, there were no major uranium mining operations in the state, though plans existed to restart production.[194]

Electricity generation

Colorado’s high Rocky Mountain ridges and eastern plains offer wind power potential, and geologic activity in the mountain areas provides the potential for geothermal power development. Much of the state is sunny and could produce solar power. Major rivers flowing from the Rocky Mountains offer hydroelectric power resources.[citation needed]

Culture

Arts and film

Several film productions have been shot on location in Colorado, especially prominent Westerns like True Grit, The Searchers, City Slickers, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and My Life With the Walter Boys. Several historic military forts, railways with trains still operating, and mining ghost towns have been used and transformed for historical accuracy in well-known films. There are also several scenic highways and mountain passes that helped to feature the open road in films such as Vanishing Point, Bingo and Starman. Some Colorado landmarks have been featured in films, such as The Stanley Hotel in Dumb and Dumber and The Shining and the Sculptured House in Sleeper. In 2015, Furious 7 was to film driving sequences on Pikes Peak Highway in Colorado. The TV adult-animated series South Park takes place in central Colorado in the titular town. Additionally, the TV series Good Luck Charlie was set, but not filmed, in Denver, Colorado.[195] The Colorado Office of Film and Television has noted that more than 400 films have been shot in Colorado.[196]

There are also several established film festivals in Colorado, including Aspen Filmfest and Aspen Shortsfest, Boulder International Film Festival, Castle Rock Film Festival, Denver Film Festival, Festivus Film Festival, Mile High Horror Film Festival, Moondance International Film Festival, Mountainfilm in Telluride, Rocky Mountain Women’s Film Festival, and Telluride Film Festival. On March 27, 2025, it was announced Sundance Film Festival would move to Boulder starting in 2027 after reaching a deal for a ten-year duration.[citation needed]

Many notable writers have lived or spent extended periods in Colorado. 5280, a Denver magazine, wrote in 2015 that Kent Haruf is “widely considered [to be] Colorado’s finest novelist”; Haruf set his novels in the fictional high plains Colorado town of Holt.[197] Beat Generation writers Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady lived in and around Denver for several years each.[198] Irish playwright Oscar Wilde visited Colorado on his tour of the United States in 1882, writing in his 1906 Impressions of America that Leadville was “the richest city in the world. It has also got the reputation of being the roughest, and every man carries a revolver.”[199][200]

Cuisine

Colorado is known for its Southwest and Rocky Mountain cuisine, with Mexican restaurants found throughout the state.[citation needed]

Boulder was named America’s Foodiest Town 2010 by Bon Appétit.[201] Boulder, and Colorado in general, is home to several national food and beverage companies, top-tier restaurants and farmers’ markets. Boulder also has more Master Sommeliers per capita than any other city, including San Francisco and New York.[202] Denver is known for steak, but now has a diverse culinary scene with many restaurants.[203]

Polidori Sausage is a brand of pork products available in supermarkets, which originated in Colorado, in the early 20th century.[204]

The Food & Wine Classic is held annually each June in Aspen. Aspen also has a reputation as the culinary capital of the Rocky Mountain region.[205]

Wine and beer

Colorado wines include varietals that have attracted favorable notice from outside the state.[206] With wines made from traditional Vitis vinifera grapes along with wines made from cherries, peaches, plums, and honey, Colorado wines have won top national and international awards for their quality.[207] Colorado’s grape growing regions contain the highest elevation vineyards in the United States,[208] with most viticulture in the state practiced between 4,000 and 7,000 feet (1,219 and 2,134 m) above sea level. The mountain climate ensures warm summer days and cool nights. Colorado is home to two designated American Viticultural Areas of the Grand Valley AVA and the West Elks AVA,[209] where most of the vineyards in the state are located. However, an increasing number of wineries are located along the Front Range.[210] In 2018, Wine Enthusiast Magazine named Colorado’s Grand Valley AVA in Mesa County, Colorado, as one of the Top Ten wine travel destinations in the world.[211]

Colorado is home to many nationally praised microbreweries,[212] including New Belgium Brewing Company, Odell Brewing Company, and Great Divide Brewing Company. The area of northern Colorado near and between the cities of Denver, Boulder, and Fort Collins is known as the “Napa Valley of Beer” due to its high density of craft breweries.[213]

Marijuana and hemp